Is Hell Real? A Loving God, Human Freedom, and What Jesus Taught

Is hell real? Explore how a loving God allows hell, how Jesus taught about it, and why the Church has always believed it matters.

Over my adult lifetime, I have had a handful of friends tell me that they did not believe that hell existed. Most of them said that a loving God would never send people to an eternity of suffering. Others believed that the concept of hell was invented by the Church to control people. I have also come across ideas online where Christianity is blended with Hinduism or Buddhism, suggesting that we return in future lives until we learn our lessons and eventually evolve our way into heaven. All of this made me want to pause and write about hell—not to scare anyone, but to share what the Church actually teaches, in case it helps someone who is wrestling with doubts or confusion.

I don’t think about hell very often. I believe it exists, and I believe it is a real possibility for me—because only God knows my heart and how my life will ultimately be judged. Still, I think far more about heaven. I find myself drawn to the hope of eternity in the bliss of the Beatific Vision—the direct vision of God, face to face. Most of my spiritual attention, though, is focused on the here and now: trying, imperfectly, to love God and love others. That is not always easy. I can be selfish. I can be lazy. But I do try, each day, to take another small step closer to God.

Was Hell Invented by the Church to Control People?

To answer that question honestly, we have to go back well before the institutional Church ever existed.

In the Old Testament, early references to life after death speak of Sheol, the realm of the dead (found especially in the Psalms and in Job). Sheol was not heaven or hell as we later understand them. It was a shadowy state where the dead simply existed, without the fullness of life or communion with God. At this early stage, there was no clear sense of judgment immediately after death.

Over time—still before Jesus and before the Christian Church—Israel’s understanding began to deepen. As faith in God’s justice matured, it became increasingly difficult to believe that the righteous and the wicked would ultimately share the same destiny. Jewish thought began to see Sheol as having a distinction: a place of rest for the righteous and a place of distress for the wicked, still temporary, still awaiting a final judgment. By the time we reach the Book of Daniel, this development becomes explicit: “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.” (Daniel 12:2)

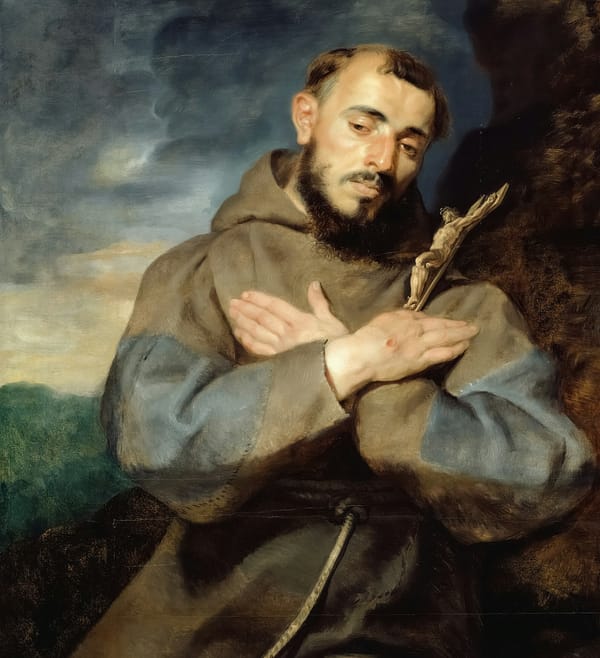

This matters. The idea of judgment after death did not suddenly appear centuries later as a tool of control. It was already present within Judaism itself. Jesus, however, speaks about hell more than anyone else in Scripture. He uses powerful images familiar to his listeners: Gehenna (a real valley associated with destruction and exclusion), “outer darkness,” “weeping and gnashing of teeth,” and “eternal fire.” Most strikingly, Jesus explicitly contrasts eternal punishment and eternal life: “And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” (Matthew 25:46)

Early Christians did not debate whether hell existed. They debated how to understand it—the imagery, the meaning of fire—but not its reality. St. Augustine (354–430 AD), for example, described hell as a state of eternal separation freely chosen by the soul that refuses God. No major orthodox Church Father taught that hell was imaginary.

It is also worth remembering that the earliest Christians were not using fear to gain power. They were persecuted, imprisoned, tortured, and killed. They believed in hell while they themselves were enduring what felt like hell on earth. The idea that hell was invented as a mechanism of control simply does not hold up historically.

How Can a Loving God Create Hell?

One simple—but helpful—way to think about this is to say that heaven is union with God, and hell is the definitive absence of that union.

In heaven, we experience the Beatific Vision: seeing God “face to face” and sharing fully in his divine life, truth, and love. Hell, by contrast, is the tragic state of choosing separation from God. The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains it this way:

“To die in mortal sin without repenting and accepting God’s merciful love means remaining separated from him forever by our own free choice.” (CCC §1033)

There are two crucial truths here. First, God gives us the extraordinary gift of free will. We are not robots. We can open our hearts to grace, respond to Christ knocking at the door of our souls, or we can resist him. Love cannot be forced. God will not coerce us into loving him or loving others. Second, God is endlessly loving and merciful. He gives us every opportunity, right up to our final breath, to repent and ask for forgiveness. Those who are lost are not people whom God refuses to forgive; they are people who reject his mercy until the end.

C. S. Lewis captured this truth memorably when he wrote, “The doors of hell are locked on the inside.” What he meant is that hell is not primarily a punishment imposed by God, but a state freely chosen and clung to by the human person. God does not trap souls in hell. Souls refuse God.

Why Hell Actually Protects God’s Love

This may sound surprising, but without hell, God would not be a loving Father—he would be a tyrant.

If no matter how we lived, no matter how much evil we committed, no matter how deeply we rejected love and truth, God simply forced everyone into heaven, then freedom would be an illusion. Love would be automatic. Evil would have no real consequences. The suffering inflicted by the unjust would ultimately mean nothing. Without hell, our moral choices would be meaningless. Victims of injustice would never truly be vindicated. Hell, tragic as it is, safeguards human dignity because it means our choices matter—now and forever.

At the same time, the Church is absolutely clear about this: God wants all of us to be saved. Every person receives the graces needed for salvation. But grace must be received; it cannot be forced. No matter how many times we fall, no matter how serious our sins, God is always ready to forgive. Venial sins can always be confessed in prayer, and mortal sins can always be forgiven through the Sacrament of Reconciliation. As long as we are alive, mercy remains open. We should not be afraid.

As St. Faustina Kowalska reminds us with such hope:

“There is no sinner in the world, however great, who should despair of the mercy of God.”

That, ultimately, is why the Church speaks about hell—not to frighten us, but to take love, freedom, and mercy seriously, and to invite us again and again to choose life.

Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam.